A look at the summer lives of four undergrads working on an environmental development project with the Foundation for Ecological Security.

Friday, July 17, 2009: Cribs: The Village Edition

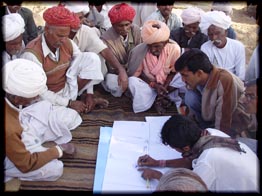

This week marked an important occasion: we moved into a village about 2 hours away from Udaipur and began working on our project. FES has asked us to make an assessment of one particular region with the eventual goal of developing a relationship with those communities and implementing environmental projects there. Our work this week mostly consisted of holding meetings with community members (all men) to create a map of the community’s resources and to get a general overview of life in the village. The meetings went well, although it can get really frustrating to watch people have an animated conversation in an inaccessible language and have to keep interjecting “what did he just say?” or “can you ask this?”. It’s hard not to feel like things would be much easier for everyone if the white girl in the corner with her notebook and expression of earnest confusion would just go sit in the jeep and eat biscuits. But we persevere, and so far the work is going well.

This week marked an important occasion: we moved into a village about 2 hours away from Udaipur and began working on our project. FES has asked us to make an assessment of one particular region with the eventual goal of developing a relationship with those communities and implementing environmental projects there. Our work this week mostly consisted of holding meetings with community members (all men) to create a map of the community’s resources and to get a general overview of life in the village. The meetings went well, although it can get really frustrating to watch people have an animated conversation in an inaccessible language and have to keep interjecting “what did he just say?” or “can you ask this?”. It’s hard not to feel like things would be much easier for everyone if the white girl in the corner with her notebook and expression of earnest confusion would just go sit in the jeep and eat biscuits. But we persevere, and so far the work is going well.

The living situation in the village is also better than expected; we have electricity (and a generator that helps protect against the frequent power outtages), running water (this one is actually pretty iffy, there have been some close calls with the toilet), and meals are provided. It should be mentioned that Asha is hands-down winning in terms of food consumption in India. This thoroughly endears her to every person who has cooked for us, and makes some of us look really bad. Skipping a meal is absolutely out of the question here, and people look shocked and a little frightened when one of us says that we’re not hungry. We’ve figured out a variety of ways to cope though (see Alice’s post on tiffin removal techniques).

The next two weeks will be similarly scheduled, with us “in the field” for the majority of week days and returning to Udaipur close to the weekend, so we won’t be close to a computer to update the blog frequently. We’ll update as much as we can though, and wish us luck seeing the solar eclipse on Wednesday!

Friday, July 24, 2009: “This is Truly A Most Auspicious Day”

I managed to declare this phrase immediately before stepping into a large pile of cowshit in the middle of the street – but truly this week has been a little of the magical as well as mundane.

I managed to declare this phrase immediately before stepping into a large pile of cowshit in the middle of the street – but truly this week has been a little of the magical as well as mundane.

The “auspicious day” in question was the 22nd of July and our musings on it’s significance were largely due to the solar eclipse which Lizzy valiantly woke up at 5:30 am to run outside to catch only to return to bed defeated five minutes later declaring it was too cloudy to see anything. However, that was just the beginning.

Later on in the day during a village exercise in a place called Jakara Lizzy and I attempted to befriend a group of teenage girls. While at first they were painfully shy, as time went on we tried asking them questions that had been translated into Hindi for us by one of our colleagues, and we soon began to laugh together over our complete unintelligbleness (although it is quite possible they were laughing at us). They even taught us a game which involves picking up stones, similar to jacks, and at the end, as you do, we took a group photo with a goat.

That night we visited the house of our driver, Sunder, in the village which we were staying in. The house was made entirely of mud/clay and had an indoor stove which smelled amazing but made my eyes water the entire time. His 100 year old grandfather was there, we drank buffalo milk (delicious!) as well as something very akin to vomit that I made the mistake of taking seconds of to be polite. As we left an electrical storm lit up the entire sky, at times making the night look like daytime and sending clear lightning bolts across the sky into the forests and hills beyond.

Then, naturally, came the cowshit – sending me reeling hysterically holding on to Ari trying to scrape it off as we all just stopped and laughed at the general absurdity and irony of the proclamation I had just made.

As well as just the fact that, well, shit guys, we are in India.

Hampered by the complexities of working in a foreign country, an unknown language and an often alien culture, I found weaving together my picture of the work of the Veerni Project was similar to the process of creating the intricate quilted wall hangings made by the women of Rajasthan – a process in which the final design appears only slowly. My first priority was to develop a thorough understanding of the NGO I am working with, its strengths, weaknesses, needs and capacity.

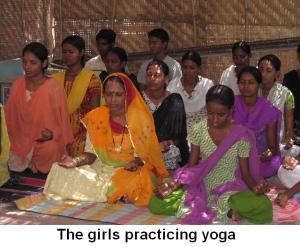

Hampered by the complexities of working in a foreign country, an unknown language and an often alien culture, I found weaving together my picture of the work of the Veerni Project was similar to the process of creating the intricate quilted wall hangings made by the women of Rajasthan – a process in which the final design appears only slowly. My first priority was to develop a thorough understanding of the NGO I am working with, its strengths, weaknesses, needs and capacity. These women are the human capital that is so often wasted in an area that has some of India’s lowest female literacy rates, female to male sex ratios and health indicators. And yet behind the gloomy statistics there lies a wealth of potential. Conducting interviews of some of the girls attending the Veerni hostel I met Shoba Choudhary, a seventeen-year-old from Rajwa village, who has been at the hostel for one year. Rajwa suffers from all the blights on women that plague one of India’s most underdeveloped states: the female literacy rate is 3.69% and the village population is 580 women to 611 men, clearly showing the number of ‘missing women’. Yet despite being married at eight, and now under pressure from her fellow villagers to give up her education and return to her family, Shoba displayed a quiet but impressive confidence and self-knowledge. ‘Education is a girl’s true friend’ she said, and talked of her ambition to attend college, pass the tough civil service exams and work for the government of Rajasthan. Only time will tell if Shoba can overcome the pressure from her village and achieve her ambitions, but her intelligence and maturity are a sign of the immense human capital Veerni is working to cultivate.

These women are the human capital that is so often wasted in an area that has some of India’s lowest female literacy rates, female to male sex ratios and health indicators. And yet behind the gloomy statistics there lies a wealth of potential. Conducting interviews of some of the girls attending the Veerni hostel I met Shoba Choudhary, a seventeen-year-old from Rajwa village, who has been at the hostel for one year. Rajwa suffers from all the blights on women that plague one of India’s most underdeveloped states: the female literacy rate is 3.69% and the village population is 580 women to 611 men, clearly showing the number of ‘missing women’. Yet despite being married at eight, and now under pressure from her fellow villagers to give up her education and return to her family, Shoba displayed a quiet but impressive confidence and self-knowledge. ‘Education is a girl’s true friend’ she said, and talked of her ambition to attend college, pass the tough civil service exams and work for the government of Rajasthan. Only time will tell if Shoba can overcome the pressure from her village and achieve her ambitions, but her intelligence and maturity are a sign of the immense human capital Veerni is working to cultivate. My FSD internship here in Jodhpur is with an NGO called UNNATI (the word unnati means “progress”) and is centered on their disaster risk reduction program. The major disaster here in the desert of Western Rajasthan is drought. My previous experience has dealt with hurricanes, earthquakes and wildfires, which tend to be very visible events with a clear beginning and end. It is easy to see their impact because you can clearly see the difference from before and after the disaster; it’s dramatic and typically gets a lot of attention when it happens. Drought is different because it has no clear beginning and end, and so its impact is more difficult to see. It becomes a regular part of people’s daily lives, and therefore doesn’t seem as dramatic and gets less attention. It’s insidious and gets to the true nature of disasters as more than just one-time events.

My FSD internship here in Jodhpur is with an NGO called UNNATI (the word unnati means “progress”) and is centered on their disaster risk reduction program. The major disaster here in the desert of Western Rajasthan is drought. My previous experience has dealt with hurricanes, earthquakes and wildfires, which tend to be very visible events with a clear beginning and end. It is easy to see their impact because you can clearly see the difference from before and after the disaster; it’s dramatic and typically gets a lot of attention when it happens. Drought is different because it has no clear beginning and end, and so its impact is more difficult to see. It becomes a regular part of people’s daily lives, and therefore doesn’t seem as dramatic and gets less attention. It’s insidious and gets to the true nature of disasters as more than just one-time events. UNNATI did not originally do this kind of work. Instead, the organization has traditionally worked to empower the Dalits, also known as the “untouchables”. In India’s ancient caste system, the Dalits were given what were considered the dirty jobs like dealing with waste and corpses, and were thus seen as permanently polluted and literally untouchable, and were treated as sub-human.

UNNATI did not originally do this kind of work. Instead, the organization has traditionally worked to empower the Dalits, also known as the “untouchables”. In India’s ancient caste system, the Dalits were given what were considered the dirty jobs like dealing with waste and corpses, and were thus seen as permanently polluted and literally untouchable, and were treated as sub-human. Many of my Indian colleagues are ashamed of the continued discrimination against Dalits. Speaking with Indians about Obama’s election back in my home country, a lot of them seem to think such problems in America are all over and only India is dealing with negative discrimination now. I try to tell them it’s not that simple. As proud as I was to see Obama win on November 4th, I was disappointed and ashamed at the passage of Proposition 8 in California and similar measures in other states.

Many of my Indian colleagues are ashamed of the continued discrimination against Dalits. Speaking with Indians about Obama’s election back in my home country, a lot of them seem to think such problems in America are all over and only India is dealing with negative discrimination now. I try to tell them it’s not that simple. As proud as I was to see Obama win on November 4th, I was disappointed and ashamed at the passage of Proposition 8 in California and similar measures in other states. Following the introduction to my new family, I was to start my internship with the Jal Bhagirathi Foundation (JBF) the next day. Abi, my co-intern, and I arrived in good spirits, ready for organizational integration. We immediately set out with Sateesh, who is responsible for the Agoli Block Women’s Self-Help Groups (SHGs), to visit the Vishnu Nagar and Jashti villages. Our mode of transportation was an open-door jeep, which lacked seatbelts, but came fully equipped with a driver who had relinquished any sense of danger probably at birth. For anyone who has not traveled by open-air vehicle through a desert before, the best way to simulate the experience would be to turn on your hair drier and blast your face for two hours.

Following the introduction to my new family, I was to start my internship with the Jal Bhagirathi Foundation (JBF) the next day. Abi, my co-intern, and I arrived in good spirits, ready for organizational integration. We immediately set out with Sateesh, who is responsible for the Agoli Block Women’s Self-Help Groups (SHGs), to visit the Vishnu Nagar and Jashti villages. Our mode of transportation was an open-door jeep, which lacked seatbelts, but came fully equipped with a driver who had relinquished any sense of danger probably at birth. For anyone who has not traveled by open-air vehicle through a desert before, the best way to simulate the experience would be to turn on your hair drier and blast your face for two hours. Ironically, our project has little to do with JBF’s core operations; rather, we have been instructed to develop a system for encouraging micro-enterprise businesses within their SHGs. These groups are bodies designed to build social and financial capital in disadvantaged communities; they have been integral to the microfinance movement within India since the 1980’s. Originally, they were established to allow the poor access to basic monetary systems, including savings and credit, by dispersing the risk amongst many women. Over time, they have grown into social empowerment tools for their members, and they are currently regarded as mechanisms which could facilitate diversification vis-à-vis alternative livelihoods and income generating activities (ALIGA). JBF has been establishing SHGs for about two years and presently operate a total of 54 groups. Predictably however, they are unsophisticated and wanting in comparison to their counterparts to the South, who have been operating in earnest for over 15. Both Vishnu Nagar and Jashti are among the A grade JBF SHGs, yet nonetheless appear woefully behind the progress in the rest of India.

Ironically, our project has little to do with JBF’s core operations; rather, we have been instructed to develop a system for encouraging micro-enterprise businesses within their SHGs. These groups are bodies designed to build social and financial capital in disadvantaged communities; they have been integral to the microfinance movement within India since the 1980’s. Originally, they were established to allow the poor access to basic monetary systems, including savings and credit, by dispersing the risk amongst many women. Over time, they have grown into social empowerment tools for their members, and they are currently regarded as mechanisms which could facilitate diversification vis-à-vis alternative livelihoods and income generating activities (ALIGA). JBF has been establishing SHGs for about two years and presently operate a total of 54 groups. Predictably however, they are unsophisticated and wanting in comparison to their counterparts to the South, who have been operating in earnest for over 15. Both Vishnu Nagar and Jashti are among the A grade JBF SHGs, yet nonetheless appear woefully behind the progress in the rest of India. However, even possessing this knowledge cannot dampen the sense of advancement, ambition and optimism radiating from the women within these groups. Not all possess this glow, but presumably the ones that do will pass it on to those yet to fully comprehend their own potential. The Vishnu Nagar women have recently bought a mechanised flour mill for the bajra (a grain similar to, but coarser than wheat) grown in their fields.

However, even possessing this knowledge cannot dampen the sense of advancement, ambition and optimism radiating from the women within these groups. Not all possess this glow, but presumably the ones that do will pass it on to those yet to fully comprehend their own potential. The Vishnu Nagar women have recently bought a mechanised flour mill for the bajra (a grain similar to, but coarser than wheat) grown in their fields.